The Method Episode #14

The Value Proposition Canvas

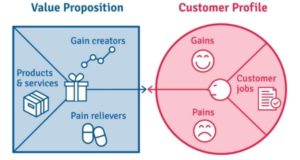

The value proposition canvas is a tool that helps you create products and services people want and will pay for.

The canvas starts with the customer profile. It assumes we have jobs, todo. Each job causes us pain and offers us gain.

Let us say my job is to get fit enough to compete in a 10km running race.

My pains are:

• Training outside in shitty weather

• Shoes that give me blisters

• Feeling unmotivated

• Nervous about competing in a race

My gains are:

• Getting fit

• Feeling good about myself

• Achievement to show off on Instagram

With this knowledge, a business can create a product or service that will help me complete my job with the product canvas.

The business starts by listing the product or service features it thinks will help.

Service: A running membership. That includes a gait assessment, discounted running shoes, weekly fun runs, an online community (FB Group), and indoor gym access.

Then the business maps their service features to the pains and gains of the potential customer (me).

Gain Creators

• We track and share your progress each week, so you’ll know you’re getting fitter.

• You’ll meet new people and receive peer support that’ll make you feel good about yourself

• Each fun run is photographed for you to share on social media

Pain Relievers

• Our gait assessment will ensure you find the perfect running shoe for you

• Access to our indoor gym means you can train in any weather conditions

• Our running community will keep you motivated and supported

• Our weekly fun-runs will get you used to competition

I’ve used this canvas multiple times to iterate current services and create new ones. You’ll often find a miss-match between what you think your customers want and what they actually need and want.

If you’re interested, this video and this blog give a more in-depth explanation of the canvas.

High-School Parties

It took me a long time to see the benefits of building a network.

Networking sounded too cheesy/corporate and energy-draining for me to care about.

But I was wrong. It’s the opposite of that. Extending on optionality, which we talked about a few weeks back. Networking costs little and gives you a ton of upside.

A cold email, a quick coffee, or a DM slide can lead to an infinitely valuable amount of opportunities and friendship.

The problem is cold out-reach requires us to ask. Which we don’t like doing.

But there’s another way. Gary Vee calls this the high school party strategy.

The mid-tier cool kids at school throw parties while their parents are away to get clout.

We can network the same way by being the connector.

What you do is host an event that brings interesting people together. By creating value for everyone else, you will be seen as valuable.

Sam Parr is a well-connected guy. But he didn’t use to be. At one point, he was homeless. Until he started putting on conferences with high-profile speakers.

He couldn’t afford to pay them, so instead used the profiles of the speakers to convince them to come. XYZ is speaking, and you’ll get a chance to talk to them.

At every event, he’d put on all the speakers in a room together for a few hours. Giving them the chance to connect and vent about the different issues they faced. This opportunity was infinitely more valuable to them than a speaking fee.

And Sam built his network by being the creator of that value.

“Curiosity is the intrinsic motivation that keeps you going.”

~ Sahil Bloom

Problems With Prediction Errors

Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked – Warren Buffett

Our way of life compels us to make predictions.

We make daily business decisions based on past events. Assuming those events and circumstances will repeat.

95% or 99% of the time, those predictions are accurate.

Mathematicians and scientists call this a confidence interval. Taking into account a certain number of variables, if data shows the outcome is expected to fall close to an average of past results. We can be confident this will happen again.

These confidence intervals/predictions are fine for day-to-day life. Where outcomes that fall wildly outside our expectations don’t have serious repercussions.

Like spending more than you budgeted for at the supermarket. This can add stress but isn’t catastrophic. Or can even be beneficial like how arriving 5 minutes late at the doctor, saves you time and you’re still 20 minutes early.

But when the consequences of prediction error are severe. Our probabilistic prediction methods fail.

Say your mortgage payments will increase this year due to interest rate rises. But you’re not worried because you got a 5% pay rise last year and you know you’ll get another one this year.

What happens when due to circumstances outside your control, your boss can’t afford to give you a raise. And now you can’t afford to meet your mortgage payments.

That scenario was likely not predictable. But these scenarios happen more often than we’d like to think. However, we only notice them when the outcomes (defaulting on a mortgage) are noticeable.

When the consequences of prediction error are minor. No problem. When the consequences are significant. Big problem.

To avoid big problems, we need to increase our margin of error. Or, as Warren Buffett’s mentor (Benjamin Graham) called it, the margin of safety.